Which Term Refers To The Personal Satisfaction Someone Gets From Consuming Goods And Services?

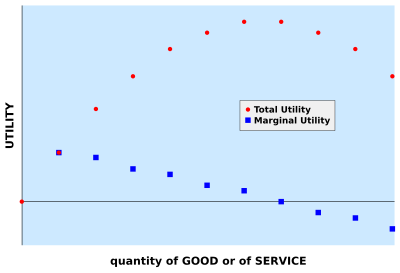

In economic science, utility is the satisfaction or do good derived by consuming a product. The marginal utility of a good or service describes how much pleasure or satisfaction is gained or lost by consumers as a outcome of the increment or decrease in consumption by i unit. There are three types of marginal utility. They are positive, negative, or zero marginal utility. For case, you like eating pizza, the second piece of pizza brings you more satisfaction than only eating one piece of pizza. It means your marginal utility from purchasing pizza is positive. However, later on eating the 2d piece you feel full, and you lot would not feel any improve from eating the third slice. This means your marginal utility from eating pizza is zero. Moreover, you lot might experience sick if yous swallow more than three pieces of pizza. At this fourth dimension, your marginal utility is negative.[ane] In other words, a negative marginal utility indicates that every unit of appurtenances or service consumed volition do more harm than expert, which will lead to the subtract of overall utility level, while the positive marginal utility indicates that every unit of goods or services consumed will increase the overall utility level.

In the context of cardinal utility, economists postulate a constabulary of diminishing marginal utility, which describes how the kickoff unit of measurement of consumption of a detail expert or service yields more utility than the 2nd and subsequent units, with a continuing reduction for greater amounts. Therefore, the fall in marginal utility as consumption increases is known as diminishing marginal utility. Economists apply this concept to make up one's mind how much of a good or service that a consumer is willing to purchase.

Marginality [edit]

The term marginal refers to a small change, starting from some baseline level. Philip Wicksteed explained the term as follows:

Marginal considerations are considerations which concern a slight increment or diminution of the stock of anything which nosotros possess or are because.[two] Another way to think of the term marginal is the cost or benefit of the adjacent unit used or consumed, for case the benefit that you might get from consuming a piece of chocolate. The key to agreement marginality is through marginal assay. Marginal assay examines the boosted benefits of an activity compared to boosted costs sustained past that same action. In practice, companies use marginal analysis to assistance them in maximizing their potential profits and often used when making decisions nearly expanding or reducing production.[three]

Utility [edit]

As a topic of economics, utility is used to measure out worth or value. Economists have usually described utility as if information technology were quantifiable, that is, as if different levels of utility could be compared along a numerical scale.[4] [5]

Initially, the term utility is equated usefulness with the production of pleasure and avoidance of pain by moral philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Factory. [six] Moreover, nether the influence of this philosophy , viewed utility as "the feelings of pleasure and pain"[vii] and farther as a "quantity of feeling" .[8]

Contemporary mainstream economical theory oftentimes defers metaphysical questions, and just notes or assumes that preference structures conforming to certain rules can be usefully proxied by associating goods, services, or their uses with quantities, and defines "utility" equally such a quantification.[nine]

In whatsoever standard framework, the aforementioned object may have different marginal utilities for different people, reflecting different preferences or individual circumstances.[ten]

Law of Diminishing marginal utility [edit]

The British economist Alfred Marshall believed that the more of something you have, the less of it yous want. This miracle is referred to as diminishing marginal utility by economists.[11] Diminishing marginal utility refers to the phenomenon that each additional unit of gain leads to an ever-smaller increment in subjective value. For example, three bites of candy are better than 2 bites, just the twentieth bite does not add much to the experience beyond the nineteenth (and could even make it worse). This effect is so well established that it is referred to equally the "constabulary of diminishing marginal utility" in economics (Gossen, 1854/1983), and is reflected in the concave shape of well-nigh subjective utility functions. This refers to the increase in utility an individual gains from increasing their consumption of a particular good. "The law of diminishing marginal utility is at the center of the explanation of numerous economic phenomena, including time preference and the value of goods ... The police says, outset, that the marginal utility of each homogeneous unit decreases as the supply of units increases (and vice versa); second, that the marginal utility of a larger-sized unit is greater than the marginal utility of a smaller-sized unit of measurement (and vice versa). The first law denotes the police force of diminishing marginal utility; the 2nd police denotes the law of increasing full utility."[12]

In modern economics, selection under conditions of certainty at a single point in time is modelled via ordinal utility, in which the numbers assigned to the utility of a particular circumstance of the private have no meaning by themselves, but which of two alternative circumstances has college utility is meaningful. With the ordinal utility, a person's preferences have no unique marginal utility, and thus whether or not the marginal utility is diminishing is not meaningful. In contrast, the concept of diminishing marginal utility is meaningful in the context of cardinal utility, which in modern economics is used in analyzing intertemporal choice, choice under uncertainty, and social welfare.

The law of diminishing marginal utility is that subjective value changes well-nigh dynamically near the nothing points and quickly levels off as gains (or losses) accumulate. And it is reflected in the concave shape of almost subjective utility functions.

Given a concave human relationship between objective gains (10-axis) and subjective value (y-axis), each one-unit of measurement gain produces a smaller increase in subjective value than the previous proceeds of an equal unit. The marginal utility, or the alter in subjective value in a higher place the existing level, diminishes every bit gains increase.[13]

Every bit the charge per unit of commodity conquering increases, the marginal utility decreases. If article consumption continues to rise, marginal utility at some point may fall to naught, reaching maximum total utility. Further increase in the consumption of commodities causes the marginal utility to become negative; this signifies dissatisfaction. For case, across some point, further doses of antibiotics would kill no pathogens at all and might even become harmful to the body. Diminishing marginal utility is traditionally a microeconomic concept and oftentimes holds for an individual, although the marginal utility of a practiced or service might exist increasing equally well. For case, dosages of antibiotics, where having likewise few pills would leave bacteria with greater resistance, only a full supply could issue a cure.

As suggested elsewhere in this article, occasionally, one may come across a situation where marginal utility increases even at a macroeconomic level. For example, providing a service may just exist feasible if it is accessible to most or all of the population. The marginal utility of a raw cloth required to provide such a service will increase at the "tipping bespeak" at which this occurs. This is like to the position with huge items such as shipping carriers: the numbers of these items involved are then pocket-size that marginal utility is no longer a helpful concept, as in that location is merely a unproblematic "yes" or "no" determination.

Marginalist theory [edit]

Marginalism explains selection with the hypothesis that people make up one's mind whether to upshot any given alter based on the marginal utility of that change, with rival alternatives beingness chosen based upon which has the greatest marginal utility.

Market price and diminishing marginal utility [edit]

If an individual possesses a good or service whose marginal utility to him is less than that of some other good or service for which he could trade information technology, then it is in his involvement to outcome that trade. Of course, as one thing is sold and another is bought, the respective marginal gains or losses from further trades volition alter. If the marginal utility of one affair is diminishing, and the other is not increasing, all else being equal, an individual will need an increasing ratio of that which is acquired to that which is sacrificed. One important manner in which all else might not exist equal is when the use of the i good or service complements that of the other. In such cases, substitution ratios might be constant.[xiv] If any trader tin can better his position by offering a trade more favorable to complementary traders, then he volition do so.

In an economy with money, the marginal utility of a quantity is simply that of the all-time good or service that information technology could purchase. In this fashion information technology is useful[ weasel words ] for explaining supply and demand, likewise equally essential aspects of models of imperfect competition.

Paradox of water and diamonds [edit]

The "paradox of water and diamonds" is well-nigh commonly associated with Adam Smith,[fifteen] though it was recognized by before thinkers.[16] The apparent contradiction lies in the fact that water possesses a lower economic value than diamonds, even though water is far more vital to human existence. Smith suggested that there was an irrational separate betwixt the 'utilise value' of something and the 'exchange value'. The things which have the greatest value in apply frequently have trivial or no value in substitution; and besides, things which have the greatest value in substitution take ofttimes picayune or no value in apply. Zilch is more useful than water: merely it will purchase scarcely anything. A diamond has hardly any applied value in apply, but a great quantity of other goods may exist had in substitution for it.[17]

Price is determined by both marginal utility and marginal cost, and hither is the key to the paradox.[ weasel words ] The marginal cost of water is lower than the marginal cost of diamonds. That is not to say that the price of any good or service is only a office of the marginal utility that it has for any one individual or for some ostensibly typical individual. Rather, individuals are willing to trade based upon the respective marginal utilities of the goods that they take or desire (with these marginal utilities being distinct for each potential trader), and prices thus develop constrained by these marginal utilities.[ commendation needed ]

Marginalism limitations [edit]

Marginalism has many limitations like many economic theories. Economists often question the if people human activity as they are portrayed within the theory. Agreement what is giving someone a specific amount of utility is extremely complex and varies from person to person and may not be stable.[18] Another limitation is in regard to the way marginal alter is measured. Measuring money is one of the simplest ways to analyse marginalism due to not having whatever other substitute. Although the limitation tin can be seen when attempting to measure the utility derived from other consumables such as food as there are too many substitutes and once over again preferences tin can limit the accurateness.[19]

Quantified marginal utility [edit]

Nether the special case in which usefulness can be quantified, the modify in utility of moving from land to state is

Moreover, if and are distinguishable by values of but one variable which is itself quantified, and then it becomes possible to speak of the ratio of the marginal utility of the change in to the size of that change:

Diminishing marginal utility, given quantification

(where "c.p." indicates that the only independent variable to change is ).

Mainstream neoclassical economic science will typically assume that the limit

exists, and utilize "marginal utility" to refer to the partial derivative

- .

Accordingly, diminishing marginal utility corresponds to the condition

-

.

History [edit]

The concept of marginal utility grew out of attempts past economists to explicate the determination of cost. The term "marginal utility", credited to the Austrian economist Friedrich von Wieser by Alfred Marshall,[20] was a translation of Wieser's term "Grenznutzen" (border-use).[21] [22]

Proto-marginalist approaches [edit]

Perhaps the essence of a notion of diminishing marginal utility can be establish in Aristotle'southward Politics, wherein he writes

external goods have a limit, like any other instrument, and all things useful are of such a nature that where there is also much of them they must either do harm, or at whatsoever rate be of no use[23]

There has been marked disagreement about the evolution and role of marginal considerations in Aristotle's value theory.[24] [25] [26] [27] [28]

A great diverseness of economists have concluded that in that location is some sort of interrelationship between utility and rarity that affects economic decisions, and in turn informs the decision of prices. Diamonds are priced higher than h2o considering their marginal utility is higher than h2o .[29]

Eighteenth-century Italian mercantilists, such equally Antonio Genovesi, Giammaria Ortes, Pietro Verri, Marchese Cesare di Beccaria, and Count Giovanni Rinaldo Carli, held that value was explained in terms of the general utility and of scarcity, though they did not typically work-out a theory of how these interacted.[30] In Della moneta (1751), Abbé Ferdinando Galiani, a pupil of Genovesi, attempted to explicate value as a ratio of ii ratios, utility and scarcity, with the latter component ratio being the ratio of quantity to use.

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, in Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution de richesse (1769), held that value derived from the full general utility of the class to which a adept belonged, from comparing of present and futurity wants, and from predictable difficulties in procurement.

Like the Italian mercantists, Étienne Bonnot, Abbé de Condillac, saw value as determined by utility associated with the class to which the good belong, and by estimated scarcity. In De commerce et le gouvernement (1776), Condillac emphasized that value is not based upon cost just that costs were paid because of value.

This final point was famously restated by the Nineteenth Century proto-marginalist, Richard Whately, who in Introductory Lectures on Political Economic system (1832) wrote

It is not that pearls fetch a high cost because men have dived for them; just on the contrary, men dive for them because they fetch a high price.[31]

(Whatley'south student Senior is noted below as an early marginalist.)

Marginalists before the Revolution [edit]

The offset unambiguous published argument of any sort of theory of marginal utility was past Daniel Bernoulli, in "Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis".[32] This newspaper appeared in 1738, but a draft had been written in 1731 or in 1732.[33] [34] In 1728, Gabriel Cramer had produced fundamentally the same theory in a private letter.[35] Each had sought to resolve the St. Petersburg paradox, and had concluded that the marginal desirability of coin decreased as it was accumulated, more specifically such that the desirability of a sum were the natural logarithm (Bernoulli) or square root (Cramer) thereof. However, the more than general implications of this hypothesis were not explicated, and the work fell into obscurity.

In "A Lecture on the Notion of Value equally Distinguished Not But from Utility, but also from Value in Exchange", delivered in 1833 and included in Lectures on Population, Value, Poor Laws and Rent (1837), William Forster Lloyd explicitly offered a full general marginal utility theory, but did not offer its derivation nor elaborate its implications. The importance of his statement seems to have been lost on anybody (including Lloyd) until the early 20th century, by which fourth dimension others had independently developed and popularized the same insight.[36]

In An Outline of the Science of Political Economy (1836), Nassau William Senior asserted that marginal utilities were the ultimate determinant of demand, yet apparently did not pursue implications, though some interpret his work as indeed doing just that.[37]

In "De la mesure de 50'utilité des travaux publics" (1844), Jules Dupuit practical a conception of marginal utility to the trouble of determining bridge tolls.[38] [ non-primary source needed ]

In 1854, Hermann Heinrich Gossen published Die Entwicklung der Gesetze des menschlichen Verkehrs und der daraus fließenden Regeln für menschliches Handeln, which presented a marginal utility theory and to a very large extent worked-out its implications for the behavior of a market economy. Notwithstanding, Gossen's work was non well received in the Deutschland of his time, most copies were destroyed unsold, and he was most forgotten until rediscovered later the so-called Marginal Revolution.[ citation needed ]

Marginal Revolution [edit]

Marginalism eventually found a foothold by way of the work of three economists, Jevons in England, Menger in Austria, and Walras in Switzerland.

William Stanley Jevons outset proposed the theory in "A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economic system" (PDF), a paper presented in 1862 and published in 1863, followed by a series of works culminating in his volume The Theory of Political Economic system in 1871 that established his reputation as a leading political economist and logician of the time. Jevons' conception of utility was in the utilitarian tradition of Jeremy Bentham and of John Stuart Mill, merely he differed from his classical predecessors in emphasizing that "value depends entirely upon utility", in particular, on "concluding utility upon which the theory of Economic science will be found to turn."[39] He later qualified this in deriving the consequence that in a model of exchange equilibrium, price ratios would be proportional not merely to ratios of "final degrees of utility," but also to costs of product.[40] [41]

Carl Menger presented the theory in Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (translated as Principles of Economics) in 1871. Menger'south presentation is specially notable on ii points. First, he took special pains to explain why individuals should be expected to rank possible uses and then to employ marginal utility to decide amongst trade-offs. (For this reason, Menger and his followers are sometimes called "the Psychological School", though they are more frequently known as "the Austrian School" or equally "the Vienna School".) Second, while his illustrative examples present utility equally quantified, his essential assumptions practice not.[42] (Menger in fact crossed-out the numerical tables in his own re-create of the published Grundsätze.[43]) Menger also adult the constabulary of diminishing marginal utility.[12] Menger'south work found a significant and appreciative audience.

Marie-Esprit-Léon Walras introduced the theory in Éléments d'économie politique pure, the first office of which was published in 1874 in a relatively mathematical exposition. Walras's work found relatively few readers at the time but was recognized and incorporated two decades later in the work of Pareto and Barone.[44]

An American, John Bates Clark, is sometimes likewise mentioned. Simply, while Clark independently arrived at a marginal utility theory, he did little to advance it until it was clear that the followers of Jevons, Menger, and Walras were revolutionizing economic science. Nonetheless, his contributions thereafter were profound.

Second generation [edit]

Although the Marginal Revolution flowed from the work of Jevons, Menger, and Walras, their work might have failed to enter the mainstream were information technology not for a second generation of economists. In England, the 2d generation were exemplified by Philip Henry Wicksteed, by William Smart, and by Alfred Marshall; in Austria by Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and by Friedrich von Wieser; in Switzerland by Vilfredo Pareto; and in America by Herbert Joseph Davenport and by Frank A. Fetter.

There were significant, distinguishing features amongst the approaches of Jevons, Menger, and Walras, but the second generation did not maintain distinctions forth national or linguistic lines. The work of von Wieser was heavily influenced by that of Walras. Wicksteed was heavily influenced past Menger. Fetter referred to himself and Davenport as function of "the American Psychological School", named in imitation of the Austrian "Psychological School". (And Clark'due south work from this menstruum onward similarly shows heavy influence by Menger.) William Smart began as a conveyor of Austrian School theory to English-language readers, though he vicious increasingly under the influence of Marshall.[45]

Böhm-Bawerk was mayhap the most able expositor of Menger's formulation.[45] [46] He was farther noted for producing a theory of interest and of profit in equilibrium based upon the interaction of diminishing marginal utility with diminishing marginal productivity of fourth dimension and with time preference.[47] This theory was adopted in full and then further adult by Knut Wicksell[48] and with modifications including formal disregard for time-preference past Wicksell'south American rival Irving Fisher.[49]

Marshall was the second-generation marginalist whose piece of work on marginal utility came virtually to inform the mainstream of neoclassical economic science, especially by way of his Principles of Economics, the start volume of which was published in 1890. Marshall constructed the demand curve with the aid of assumptions that utility was quantified, and that the marginal utility of money was constant (or nearly so). Like Jevons, Marshall did non see an explanation for supply in the theory of marginal utility, then he synthesized an caption of need thus explained with supply explained in a more classical way, determined by costs which were taken to exist objectively determined. Marshall later actively mischaracterized the criticism that these costs were themselves ultimately adamant by marginal utilities.[50]

Marginal Revolution and Marxism [edit]

Karl Marx acknowledged that "nothing tin can accept value, without beingness an object of utility",[51] [52] simply in his analysis "employ-value as such lies exterior the sphere of investigation of political economy",[53] with labor being the principal determinant of value under capitalism.[ non-master source needed ]

The doctrines of marginalism and the Marginal Revolution are often interpreted as somehow a response to Marxist economics.[ by whom? ] However the first volume of Das Kapital was not published until July 1867, afterward the works of Jevons, Menger, and Walras were written or well under way (Walras published Éléments d'économie politique pure in 1874 and Carl Menger published Principles of Economics in 1871); and Marx was even so a relatively minor figure when these works were completed.[ commendation needed ] Information technology is unlikely that[ weasel words ] any of them knew anything of him. (On the other hand, Friedrich Hayek and W. Due west. Bartley Iii have suggested that Marx, voraciously[ peacock prose ] reading at the British Museum, may have come beyond the works of one or more than of these figures, and that his disability to formulate a viable critique may business relationship for his failure to complete any further volumes of Kapital before his death.[54]

Withal, it is not unreasonable to suggest[ weasel words ] that the generation who followed the preceptors of the Revolution succeeded partly because they could formulate straightforward responses to Marxist economic theory. The most famous of these was that of Böhm-Bawerk, Zum Abschluss des Marxschen Systems (1896),[55] but the start was Wicksteed'south "The Marxian Theory of Value. Das Kapital: a criticism" (1884,[56] followed by "The Jevonian criticism of Marx: a rejoinder" in 1885).[57] Initially there were only a few Marxist responses to marginalism, of which the virtually famous were Rudolf Hilferding'southward Böhm-Bawerks Marx-Kritik (1904)[58] and Politicheskoy ekonomii rante (1914) past Nikolai Bukharin.[59] Nevertheless, over the class of the 20th century a considerable literature developed on the disharmonize between marginalism and the labour theory of value, with the piece of work of the neo-Ricardian economist Piero Sraffa providing an important critique of marginalism.

It might also be noted[ weasel words ] that some followers of Henry George similarly consider marginalism and neoclassical economics a reaction to Progress and Poverty which was published in 1879.[lx]

In the 1980s John Roemer and other analytical Marxists accept worked to rebuild Marxian theses on a marginalist foundation.

Reformulation [edit]

In his 1881 work Mathematical Psychics, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth presented the indifference curve, deriving its properties from marginalist theory which assumed utility to be a differentiable function of quantified goods and services. Later work attempted to generalize to the indifference curve formulations of utility and marginal utility in avoiding unobservable measures of utility.

In 1915, Eugen Slutsky derived a theory of consumer selection solely from properties of indifference curves.[61] Because of the World War, the Bolshevik Revolution, and his own subsequent loss of interest, Slutsky's work drew near no discover, simply similar piece of work in 1934 by John Richard Hicks and R. M. D. Allen[62] derived largely the same results and plant a significant audience. (Allen subsequently drew attention to Slutsky's before achievement.)

Although some of the tertiary generation of Austrian Schoolhouse economists had by 1911 rejected the quantification of utility while continuing to retrieve in terms of marginal utility,[63] most economists presumed that utility must exist a sort of quantity. Indifference curve analysis seemed to represent a mode to dispense with presumptions of quantification, albeit that a seemingly arbitrary supposition (admitted by Hicks to be a "rabbit out of a hat"[64]) almost decreasing marginal rates of commutation[65] would then accept to be introduced to take convexity of indifference curves.

For those who accustomed that indifference curve analysis superseded earlier marginal utility analysis, the latter became at best possibly pedagogically useful, but "erstwhile fashioned" and observationally unnecessary.[65] [66]

Revival [edit]

When Cramer and Bernoulli introduced the notion of diminishing marginal utility, information technology had been to address a paradox of gambling, rather than the paradox of value. The marginalists of the revolution, however, had been formally concerned with problems in which in that location was neither take chances nor uncertainty. And so too with the indifference curve analysis of Slutsky, Hicks, and Allen.

The expected utility hypothesis of Bernoulli and others was revived past various 20th century thinkers, with early contributions past Ramsey (1926),[67] von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944),[68] and Savage (1954).[69] Although this hypothesis remains controversial, it brings non only utility, but a quantified conception of utility (cardinal utility), dorsum into the mainstream of economic idea.

A major reason why quantified models of utility are influential today is that risk and incertitude have been recognized as cardinal topics in gimmicky economic theory.[seventy] Quantified utility models simplify the analysis of risky decisions considering, under quantified utility, diminishing marginal utility implies run a risk aversion.[71] In fact, many gimmicky analyses of saving and portfolio choice require stronger assumptions than diminishing marginal utility, such as the assumption of prudence, which ways convex marginal utility.[72]

Meanwhile, the Austrian School continued to develop its ordinalist notions of marginal utility analysis, formally demonstrating that from them proceed the decreasing marginal rates of substitution of indifference curves.[14]

Run into likewise [edit]

- Diminishing returns

- Economic subjectivism

- Marginalism

- Microeconomics

- Paradox of value

- Rivalry (economics)

- Shadow toll

- Theory of value (economics)

- Utility

References [edit]

- ^ "To a higher place the Margin: Agreement Marginal Utility". Investopedia . Retrieved 2021-08-31 .

- ^ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; The Common Sense of Political Economy (1910), Bk I Ch two and elsewhere.

- ^ "Agreement Marginal Analysis". Investopedia . Retrieved 2022-05-02 .

- ^ Stigler, George Joseph; The Development of Utility Theory, I and Ii, Journal of Political Economy (1950), bug iii and 4.

- ^ Stigler, George Joseph; The Adoption of Marginal Utility Theory, History of Political Economy (1972).

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy. Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Chapter I §I–Iii.

- ^ Jevons, William Stanley; "Brief Business relationship of a General Mathematical Theory of Political Economic system", Periodical of the Majestic Statistical Society v29 (June 1866) §two.

- ^ Jevons, William Stanley; Brief Business relationship of a Full general Mathematical Theory of Political Economic system, Journal of the Imperial Statistical Society v29 (June 1866) §4.

- ^ Kreps, David Marc; A Course in Microeconomic Theory, Chapter two: The theory of consumer choice and demand, Utility representations.

- ^ Davenport, Herbert Joseph; The Economics of Enterprise (1913) Ch Vii, pp. 86–87.

- ^ G.J. (2013). "The utility of bad art". Economist.

- ^ a b Polleit, Thorsten (2011-02-11) What Can the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility Teach Us?, Mises Institute

- ^ E.T. Berkman,50.East. Kahn,J.50. Livingston (2016). "Chapter 13 Valuation as a Mechanism of Cocky-Control and Ego Depletion". Self-Regulation and Ego Command. United states. pp. 255–279. ISBN978-0-12-801850-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mc Culloch, James Huston; "The Austrian Theory of the Marginal Utilise and of Ordinal Marginal Utility", Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 37 (1977) #three&4 (September).

- ^ Smith, Adam; An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) Chapter IV. "Of the Origin and Use of Money"

- ^ Gordon, Scott (1991). "The Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century". History and Philosophy of Social Scientific discipline: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN0-415-09670-7.

- ^ Alex Gendler. "The paradox of value-Akshita Agarwal".

- ^ "Marginalism | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2022-05-02 .

- ^ "Marginalism | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com . Retrieved 2022-05-02 .

- ^ Marshall, Alfred; Principles of Economic science, 3 Ch 3 Annotation.

- ^ von Wieser, Friedrich; Über den Ursprung und die Hauptgesetze des wirtschaftlichen Wertes [The Nature and Essence of Theoretical Economics] (1884), p. 128.

- ^ Wieser, Friedrich von; Der natürliche Werth [Natural Value] (1889), Bk I Ch V "Marginal Utility" (HTML).

- ^ Aristotle, Politics, Bk 7 Chapter ane.

- ^ Soudek, Josef (1952). "Aristotle'due south Theory of Substitution: An Research into the Origin of Economic Analysis". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 96 (1): 45–75. JSTOR 3143742.

- ^ Kauder, Emil (1953). "Genesis of the Marginal Utility Theory from Aristotle to the Finish of the Eighteenth Century". The Economic Periodical. 63 (251): 638–l. doi:ten.2307/2226451. JSTOR 2226451.

- ^ Gordon, Barry Lewis John (1964). "Aristotle and the Development of Value Theory". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 78 (1): 115–28. doi:10.2307/1880547. JSTOR 1880547.

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph Alois; History of Economical Analysis (1954) Part 2 Chapter i §3.

- ^ Meikle, Scott; Aristoteles' Economic Thought (1995) Capacity 1, 2, & six.

- ^ Přibram, Karl; A History of Economical Reasoning (1983).

- ^ Pribram, Karl; A History of Economical Reasoning (1983), Chapter 5 "Refined Mercantilism", "Italian Mercantilists".

- ^ Whately, Richard; Introductory Lectures on Political Economy, Being role of a course delivered in the Easter term (1832).

- ^ Bernoulli, Daniel; "Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis" in Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae five (1738); reprinted in translation as "Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk" in Econometrica 22 (1954).

- ^ Bernoulli, Daniel; letter of four July 1731 to Nicolas Bernoulli (excerpted in PDF Archived 2008-09-09 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Bernoulli, Nicolas; letter of v April 1732, acknowledging receipt of "Specimen theoriae novae metiendi sortem pecuniariam" (excerpted in PDF Archived 2008-09-09 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Cramer, Garbriel; letter of 21 May 1728 to Nicolaus Bernoulli (excerpted in PDF Archived 2008-09-09 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Seligman, East. R. A. (1903). "On Some Neglected British Economists". The Economic Journal. thirteen (51): 335–63. doi:ten.2307/2221519. hdl:2027/hvd.32044081864944. JSTOR 2221519.

- ^ White, Michael 5. (1992). "Diamonds Are Forever(?): Nassau Senior and Utility Theory". The Manchester School. threescore (1): 64–78. doi:x.1111/j.1467-9957.1992.tb00211.ten.

- ^ Dupuit, Jules (1844). "De la mesure de l'utilité des travaux publics". Annales des ponts et chaussées. 2nd series. eight.

- ^ Due west. Stanley Jevons (1871), The Theory of Political Economy, p. 111.

- ^ W. Stanley Jevons (1879, 2nd ed.), The Theory of Political Economy, p. 208.

- ^ R.D. Collison Brownish (1987), "Jevons, William Stanley," The New Palgrave: A Lexicon of Economics, v. 2, pp. 1008–09.

- ^ Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas; Utility, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1968).

- ^ Kauder, Emil; A History of Marginal Utility Theory (1965), p. 76.

- ^ Donald A. Walker (1987), "Walras, Léon" The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, five. four, p. 862.

- ^ a b Salerno, Joseph T. 1999; "The Place of Mises's Human Action in the Development of Modern Economic Thought." Quarterly Journal of Economic Idea v. ii (1).

- ^ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von. "Grundzüge der Theorie des wirtschaftlichen Güterwerthes", Jahrbüche für Nationalökonomie und Statistik v 13 (1886). Translated every bit Basic Principles of Economic Value.

- ^ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von; Kapital Und Kapitalizns. Zweite Abteilung: Positive Theorie des Kapitales (1889). Translated as Uppercase and Interest. II: Positive Theory of Capital with appendices rendered equally Farther Essays on Majuscule and Involvement.

- ^ Wicksell, Johan Gustaf Knut; Über Wert, Kapital unde Rente (1893). Translated as Value, Uppercase and Rent.

- ^ Fisher, Irving; Theory of Involvement (1930).

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph Alois; History of Economic Analysis (1954) Pt Four Ch six §4.

- ^ Marx, Karl Heinrich; Uppercase V1 Ch i §ane.

- ^ Marx, Karl Heinrich; Grundrisse (completed in 1857 though not published until much later)

- ^ Marx, Karl Heinrich: A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economic system (1859), p. 276

- ^ Hayek, Friedrich August von, with William Warren Bartley Three; The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (1988) p. 150.

- ^ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von: "Zum Abschluss des Marxschen Systems" ["On the Closure of the Marxist Organisation"], Staatswiss. Arbeiten. Festgabe für K. Knies (1896).

- ^ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; "Das Kapital: A Criticism", To-day 2 (1884) pp. 388–409.

- ^ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; "The Jevonian criticism of Marx: a rejoinder", To-twenty-four hour period iii (1885) pp. 177–79.

- ^ Hilferding, Rudolf: Böhm-Bawerks Marx-Kritik (1904). Translated every bit Böhm-Bawerk's Criticism of Marx.

- ^ Буха́рин, Никола́й Ива́нович (Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin); Политической экономии рантье (1914). Translated as The Economic Theory of the Leisure Grade.

- ^ Gaffney, Mason, and Fred Harrison: The Corruption of Economics (1994).

- ^ Слуцкий, Евгений Евгениевич (Slutsky, Yevgyeniy Ye.); "Sulla teoria del bilancio del consumatore", Giornale degli Economisti 51 (1915).

- ^ Hicks, John Richard, and Roy George Douglas Allen; "A Afterthought of the Theory of Value", Economica 54 (1934).

- ^ von Mises, Ludwig Heinrich; Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel (1912).

- ^ Hicks, Sir John Richard; Value and Capital letter, Chapter I. two"Utility and Preference" §viii, p. 23 in the 2nd edition.

- ^ a b Hicks, Sir John Richard; Value and Upper-case letter, Chapter I. "Utility and Preference" §7–8.

- ^ Samuelson, Paul Anthony; "Complementarity: An Essay on the 40th Anniversary of the Hicks-Allen Revolution in Demand Theory", Periodical of Economic Literature vol 12 (1974).

- ^ Ramsey, Frank Plumpton; "Truth and Probability" (PDF Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine), Chapter VII in The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays (1931).

- ^ von Neumann, John and Oskar Morgenstern; Theory of Games and Economical Beliefs (1944).

- ^ Savage, Leonard Jimmie: Foundations of Statistics (1954), New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Diamond, Peter, and Michael Rothschild, eds.: Dubiety in Economics (1989). Academic Printing.

- ^ Demange, Gabriel, and Guy Laroque: Finance and the Economic science of Uncertainty (2006), Ch. 3, pp. 71–72. Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Kimball, Miles (1990), "Precautionary Saving in the Small and in the Large", Econometrica, 58 (i) pp. 53–73.

Further reading [edit]

- Downey, E. H. (1910). "The Futility of Marginal Utility". Journal of Political Economy. xviii (4): 253–268. doi:ten.1086/251690. JSTOR 1820794.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Marginal utility at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marginal utility at Wikimedia Commons - Maximization of Originality

Which Term Refers To The Personal Satisfaction Someone Gets From Consuming Goods And Services?,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_utility

Posted by: browningsubtromed87.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Term Refers To The Personal Satisfaction Someone Gets From Consuming Goods And Services?"

Post a Comment